|

Michael McFadyen's Scuba Diving - SS Oakland

The SS Oakland was launched in 1890 at the Murray Brothers shipyard in Dumbarton, Scotland (a very nice little town to the north of Glasgow). The Oakland was 47 metres long, had a beam of 7 metres and displaced 398 tons. The single screw steamship was powered by a triple expansion engine built by Kincaid and Co of Greenock, Scotland (just across the Clyde) and it had a single scotch boiler. She was also rigged as a fore and aft schooner.

The new ship was built for William T. Yeager, who had a timber yard in Pyrmont in Sydney and sawmill in the Northern Rivers area of NSW. The ship was designed as a general cargo/passenger ship, presumably to carry the owner's goods. As such, the vessel had two holds with two steam winches serving a revolving steam crane.

The new ship was named after the owner's residence and sawmill on the Richmond River on the Far North Coast of New South Wales. The Oakland left Greenock, Scotland on 10 May 1890 for the trip to Australia. Under the command of Captain Rice, she took 89 days (this was possibly 81 days at sea) to travel to Sydney, arriving on 7 August 1890. She stopped over in Teneriffe (Canary Islands), St Vincent and Cape Town.

|

The Oakland

coming up Sydney Harbour |

She carried all her own coal for the journey and as additional cargo, steam engines for a new vessel built for Mr Yeager by Rock Davis at his Blackall shipyard, Brisbane Water (just north of Sydney). Of interest, Davis was later to build the TSS Belbowrie which was to later sink at South Maroubra in Sydney.

The Oakland was subjected to a quick overhaul and then entered service on 27 August 1890 under the command of Captain Benjamin Alley. She immediately commenced operations between Sydney, Newcastle and the Richmond River, doing 72 voyages in 1891. The regular skipper was Captain Alley but at times Captain Rice was in command. For three years the Oakland transported timber and general cargo to Sydney as well as supplies to the far north of the State.

On 24 June 1893 the ship collided with the PS Sydney near Bird Island off Catherine Hill Bay on the Central Coast. There was little damage to either vessel. The Marine Board of New South Wales held an enquiry into the collision. On 10 July 1893, George S. Lindeman, RN, delivered its report. They found that the master of the Oakland was at fault for poor discipline and a breach of steering and sailing rules. The master of the Sydney was also found guilty of not stopping and reversing her engines when the lights of the Oakland changed from green to red.

|  |

I think this is the Oakland

aground at Richmond River | The Oakland aground on

the southern wall of

the Richmond River bar |

Captain Alley and Captain Richard James Skinner of Sydney were reprimanded.

Captain Alley was still captain in 1894. The ship was fairly quick, on one journey she left the Richmond River at 10.24 on 24 January 1894 and arrived at Yeager's Wharf at Pyrmont, Sydney, at 2 am on 26 January 1894, a trip of just over 39 hours.

On 13 November 1898 the Oakland was sold to the North Coast Steam Navigation Company. Another ship, the St George, was also sold to NCSNC at the same time. Captain Alley remained skipper. In 1899 certain modifications to the ship were made including strengthening of the hull and the installation of a new bulkhead in hold one, dividing it into two. Captain Evans was skipper at this time.

At 6.30am on 26 August 1901 the SS Oakland hit the Richmond River bar and crashed onto the southern wall of the entrance. For five weeks the ship was stuck (see the photo at right which shows water right across the deck). Damage to the ship included holes in the hull, the stern frame was bent, the stern-post broken in three places, the port side hull damaged and many frames twisted. The Sydney Marine Underwriters' Association refloated the ship on 1 October (or possibly 2 October) and after emergency repairs at the Richmond River dockyard, she was taken to Sydney for more extensive repairs. It took three months in Morts Dock at Balmain but on 13 February 1902 she was relaunched.

|

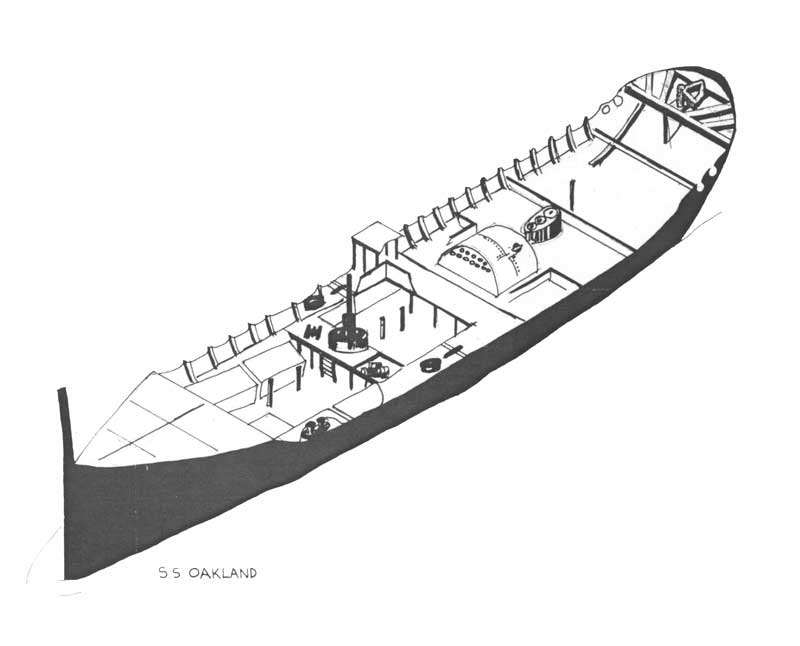

A drawing of the SS Oakland by John Riley together with his initial plotting of the wreck remains

John Riley Memorial Collection, Heritage Branch, OEH

|

The whole port side of the hull had been replaced and other work carried out. Some more work was carried out at Morts Dock in November 1902 four tanks when were installed into hold two (two on either side) to carry molasses from the northern river sugar cane refineries. The skipper around this time was Captain Beach.

This was not the only time that the SS Oakland hit the Richmond River bar. It was reported by the Chief Engineer Surveyor, James Shirra, on 9 June 1903, that the ship "has been frequently under repairs necessitated by going on the rocks at the bar or in the river".

May 1903 saw the Oakland having her annual refit in Sydney and her licence was renewed for another six months.

On 25 May 1903 at 9 pm, the SS Oakland left Sydney on what turned out to be her last voyage. She was not carrying cargo on the first part of the trip, just water ballast in her ballast tanks. She arrived in Newcastle at 5 am the next morning and loaded 300 (or perhaps 350) tons of coal, four bundles of railway tracks, 9 tons of flour, 10 tons of gravestones and other cargo. The cargo loading did not start till 3 pm. At 1am on Wednesday 27 May 1903 the Oakland left Newcastle after this short stop on her way to the Clarence and Richmond Rivers. The only passenger was the monumental stonemason, Thomas Gaites, owner of the gravestones.

The weather was a moderate to strong south-westerly with a large sea. However, the Second Mate later told a newspaper that from the time they cleared Nobbys Head (the southern headland to Newcastle Harbour), the storm was the worst he had ever experienced.

The ship passed Port Stephens Outer Light at 3.15am and within 20 minutes, the cargo shifted to port and the Oakland started to list dramatically. Despite many attempts to find the cause of the list, no reason was found by the crew or Captain. As if this was not bad enough, the ship was now taking water and slowly sinking bow first. The sail was raised in an attempt to speed and steady the ship. Captain William Slater (age 41), an employee of NCSNC for 16 years and on his last planned trip on the ship, ordered the helmsman to steer for the northern side of Cabbage Tree Island but by this time the ship was too far gone. Captain Slater decided to turn her around to make Port Stephens (a few kilometres away) and then ordered that they head for Port Stephens lighthouse. When this turn was attempted, the Oakland began to go around in circles and the funnel was almost in the water.

Nearly all shipwrecks of the 1800s and early 1900s have one thing in common, the inability to successfully launch the lifeboats because of the list of the vessel and poor design. Such was the case with the Oakland. Many attempts were made to release the boats but they remained connected to the davits.

In the end, the funnel was in the water and the crew had now clambered onto the hull. From this position they were able to release one lifeboat. Unfortunately, the waves had caused the davit to punch a hole in the lifeboat and it filled with water and when all 18 crew and passenger climbed in, it capsized. The Oakland rolled over and sank, her prop clear of the water and still slowly turning. The lifeboat was righted and three crew climbed aboard and ten crew and the passenger clung to its side, the buoyancy tanks keeping it afloat. Four crew were now missing. An attempt was made to row towards nearby Cabbage Tree Island but against the prevailing winds and seas and in a vessel totally full of water, it was impossible. Eventually seven men climbed in the boat with the rest hanging on to the side.

The seas and wind were carrying the lifeboat towards Broughton Island, about five kilometres away. As the sun rose, the cook, John Bradbury (34) died and 30 minutes later the chief engineer, A. Fisher (35) also died. At about 7.15am Captain Slater passed away and soon after, Alec Cargill (16), the officers' boy joined him. The second engineer, Robert Steel (22) was next to go when he suddenly exclaimed "This is lovely" and jumped from the boat into the raging sea. After each person died, they were put into the water and a person hanging on to the side climbed aboard the lifeboat.

By now the submerged boat was off the entrance to Esmeralda Cove on Broughton Island but rescue was near. The SS Bellinger was approaching Broughton Island from the south after unsuccessfully attempting to enter Port Stephens to shelter from the gale. Her crew had sighted wreckage and were on the lookout for survivors as they headed for refuge behind the big island. Unfortunately, time was up for Able Seaman J. Johnson (40) and he died just before the remaining seven crew were pulled aboard the rescue vessel.

Note: there is a discrepancy of one person in this report, as there were 17 crew and one passenger on board, a total of 18. Seven survived, six perished from the lifeboat and four died when the Oakland sank leaving one unaccounted for in this description of events). In July 2006 Cheryl Anderson emailed me advising that her Great Grandfather, Joseph Wilcox, was the fireman on the SS Oakland. His death certificate says that he drowned when the Oakland was wrecked in a gale on 27 May 1903. Mr Wilcox may be the missing man in terms of this account of the sinking, although he may be one of the men who died when the ship actually sank.

The Newcastle Morning Herald dated 30 May 1903 listed the survivors of the SS Oakland as:

The paper listed the dead/missing as:

* jumped overboard

# lost when boat capsized

In July 2007 Cheryl Anderson again emailed me and provided me with some information from the Newcastle Morning Herald dated 30 May 1903. She also told me that she has some other clippings and after reading them all, she advises that it seems the two fireman were sighted on deck/on the boat just before they got into the lifeboat. The lifeboat capsized soon after it hit the water and the men in it noticed that "Joe and Bob" the two fireman were missing. They also noticed that "Brooks, Lindgren and the lamp trimmer" (not sure who had the task of lamp trimming) were missing.

Another report by Able Seaman W. Jacobsen said that he "never saw anything of the two fireman or the mate". His statement also has a discrepency as he says four were lost in the first capsize, five died in the boat and one jumped overboard. He also says when the boat capsized just after leaving the ship only 13 succeeded in hanging on - this gives 17.

I am not sure where the accounts of the wreck were printed. Cheryl Anderson says that the print looks similar to the Newcastle Morning Herald cited above but they do not have dates on them and are on separate sheets of paper.

Frank Gardner of the National Shipwreck Relief Society met the survivors and presented them with clothes and sufficient funds to enable them to get home to Sydney. The survivors, Second Mate John Howes (57), Able Seaman G. Gustavson (31), Able Seaman Isaac Holm (48), Able Seaman J. E. Ohlsson, Able Seaman T. Willberg, Able Seaman W. Jacobson and the passenger Thomas Gaites, were taken on the SS Sydney via Newcastle to Sydney (the ship may have been boarded in Newcastle). Messrs Ohlsson and Holm were named on Mr Wilcox's death certificate as being witnesses.

The ship was, of course, a total write off and the North Coast Steam Navigation Company received £4,000 insurance. The wreck was located by Captain H. Warne, skipper of the Newcastle and Hunter River steamer SS Namoi. The water was said to be 12 fathoms deep (72 feet or 21 metres - it is actually a bit deeper) and the masts stuck out of the water six feet. The salvage rights to the wreck were sold to Captain Weston of Balmain, Sydney, for £40. He proposed to salvage the ship and cargo.

Using three divers (Peter Anderson, Tas Coutts and a Frenchman called Tommy), Captain Weston and his ship Maud Weston anchored over the wreck. Over a period they salvaged 100 tons of coal, the fore and after winches, the steering gear, 175 fathoms of anchor, blocks, derricks, a steam windlass and hawsers. A total of £300 worth of equipment was recovered. Already, the masts had fallen, the bridge fallen into hold two and the funnel broken off.

Captain Weston stated that he intended to refloat the ship by pumping air into the molasses tanks. This was supposed to happen in the second week of July, 1903. However, there is no record of what happened, if indeed the attempt took place. The salvage appears to have been abandoned around this time.

The Marine Court of Inquiry could find no reason for the tragedy but expressed the view that the cargo must have shifted.

|  |  |  |

A plan showing rough

location of wreck | Western Mark | South-western Mark | South-south-western Mark |

Today, the Oakland lies to the north of Cabbage Tree Island in about 27 metres of water, facing the south-west (exactly the same direction as its flee for safety). A mooring used to be located about 50 metres to the west of the wreck and a line ran from the mooring to the centre of the wreck. However, as of October 2006 the mooring is on the stern. Approximate GPS readings for the mooring are 32° 40.6878' S 152° 14.0003' E (note this is using WGS84 as datum, if you use another, see my GPS Page for what this means) and the attached diagram and marks will help you find the mooring location. For more detail, see GPS and Marks Page.

|  |

A diagram of the SS Oakland by John Riley

John Riley Memorial Collection, Heritage Branch, OEH

Click on diagram to see larger sized version | Another version of the Oakland diagram by John Riley

John Riley Memorial Collection - Heritage Branch, OEH

Click on diagram to see larger sized version |

The wreck is in one piece, with the deck totally missing as is the bridge area and funnel. The surrounding sand comes right up to a level almost equal to the normal sea level on the boat when she plied her trade and the wreck only rises two metres off the sand. From the mooring line you encounter the boiler which is almost totally buried in the sand and behind this is the triple expansion engine. On either side of the engine and boiler against the hull you will see the molasses tanks installed in November 1902.

As you swim to the stern you pass the many ribs of the hull which stick up out of the sand on either side of you. At the stern you can see the rudder turned hard to port and the tip of one propeller blade (in October 2006 this could not be seen). The stern is a much more significant part of the vessel and sits three or four metres above the sand.

|

| Kelly McFadyen and the starboard hull of the Oakland near the engine |

Swimming back along the wreck you again pass the engine and boiler before seeing the remains of the forward mast. The holds can sort of be made out and as mentioned, the tanks in number two hold can be seen. The starboard side of the ship's hull in this area is almost totally gone. Like the stern, the bow sits up higher and from the rear looks intact. However, the hull is almost totally missing from the sides of the bow and all that remains is the deck and the ribs of the hull. Despite this, it is still quite interesting as it enables you to enter easily (and safely) inside the forecastle. The bowsprit sticks up high from the vertical bow. As indicated earlier, the anchors are missing, salvaged in 1903.

|  |

| Kelly over the engine of the Oakland | The boiler of the Oakland |

The fishlife on this wreck is excellent, with catfish by the dozen in the bow, up to 30 or more porcupine fish on the sand adjacent to the wreck and red morwong all over. As well, huge schools of yellowtail float over the wreck and 20 or so squid come in off the sand. A few moray and mosaic eels inhabit the boiler and engine and nice sponges cover most parts of the wreck. All in all, a very good and interesting dive.

|  |

| The bow of the Oakland | Kelly and the mast of the Oakland |

The visibility on this dive is normally very good, about 18 metres but I have had as little as seven metres. On one dive I had some current from the south. The water in early May is about 21 degrees and October 18 degrees. I have dived this wreck with Pro Dive Nelson Bay and Hawks Nest Dive Centre. Both gave very good service.

References:

|

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005