|

Michael McFadyen's Scuba Diving - SS Duckenfield

In mid-1875 a new ship started construction in London, England. The vessel was the SS Duckenfield and the shipbuilder was J. & W. Dudgeon. The new ship was 49.1 metres long and 7.3 metres wide with a displacement of 368 tons gross. She was powered by a two cylinder vertical steam engine (also built by J. & W. Dudgeon) turning a single prop. She also had sails as an auxilary form of propulsion.

Late that year, the Duckenfield left London for Newcastle where she was due to join the fleet of J. & A. Brown. As well as delivering the ship, cargo was being carried, namely 31 wagons and 40 sets of wheels for the Minmi colliery in the Hunter Valley (interestingly, a ship called the SS Minmi was later to be wrecked off the Southern Sydney coast).

On Wednesday 16 February 1876, the SS Duckenfield arrived in Melbourne, Victoria. She was sailing as she did not have her propeller fitted (no idea why you would do this). She apparently needed to take on provisions.

|

| A photo of the SS Duckenfield |

After off-loading the cargo at Hexham, up the Hunter River, the Duckenfield was towed to Sydney to have her propeller fitted. As I mentioed above, for an unknown reason, the Duckenfield travelled to Newcastle under sail rather than steam. On 29 March 1876, the Duckenfield started work for J. & A. Brown. The vessel's regular trip was said to be from Newcastle to Sydney with occasional trips where she transported coal from the southern coalfields to Sydney. However, most of the reports I have found in newspapers show her working from Newcastle to Sydney, at least from 1878 to 1884.

On 19 June 1878 the Duckenfield sailed from Newcastle to Sydney. On Monday 5 August 1878 she arrived in Newcaslte from Sydney. For the period 1878 to 1881 she appears to have been on the Newcastle to Sydney run.

On the night of Wednesday 15 December 1880 the Duckenfield was on her way from Newcastle to Sydney with a load of coal as well as 800 sheep. During the voyage, she shipped several heavy seas which washed away and drowned 500 of them. The Captain and First Mate had a narrow eacape, the former saving himself from being carried away by clinging to a rope, while the latter managed to hold on to the rail. I find it hard to even see how the ship could carry 500 sheep, let alone 800!

|  |

A photo of the SS Duckenfield courtesy of

Warwick Taylor whose grandfather, a member

of the Coal Lumpers Union, possibly took it | A painting of the SS Duckenfield |

On the evening on Thursday 25 November 1880, the Duckenfield collied with the SS Glenelg. However, I am not sure where this happened, but I am fairly certain it happen in or near Sydney. Apparently the Glenelg almost sank. On Monday 29 November 1880 a Marine Board of Inquiry started into the accident. It concluded on Tuesday 30 November 1880. On Wednesday 1 December 1880 the Marine Board found that that both masters were at fault. They were censured and cautioned that their future conduct would be watched.

Another report was that the evidence in this case is of so conflicting a nature that the board was unable to decide upon the exact spot on which the collision occurred. It was reported that it was clear that neither vessel kept as far as was practicable on that side of the fairway or mid-channel course which lay on her own starboard hand as she should have done in accordance with the provision of section 120 of the Navigation Act. As the collision occurred in broad daylight and when the vessels were under "perfect command", the Board was of the opinion that both masters were to blame. They were therefore censured and cautioned as to their future conduct.

From the above paragraph, it appears that the collision occurred in Sydney Harbour.

On Monday 18 April 1881 the bodies of John O'Shea and John Wilson, seamen on board the Duckenfield, were found floating in the water under Dibbs wharf at Darling Harbour in Sydney Harbour. An inquest was to be held on Wednesday 20 April 1881. I have no further information on this.

At 10 pm on Sunday 19 June 1881, the Duckenfield left Sydney under the command of Captain Fetherbridge with a small steamer named the Victory in tow. The Victory was owned by Mr. Longworth, of Sydney (an old Newcastle resident). When they were off Broken Bay on the way to Newcastle, part of the Victory'sd towing gear parted and she slewed around and filled with water. She sank within 10 minutes. Mr Longworth and Mr J. McNab (formerly of Newcastle) were on the Victory at the time and very narrowly escaped being drowned. Captain Fetherbridge saw the accident and succeeded in rescuing those aboard. He stood by the spot until the craft had sunk out of sight and nothing more was visible

Mr Longworth escaped the sinking ship almost in a state of nudity, having lost everything, and was compelled to borrow a suit of clothes to go ashore wife of his safety. The lost steamer was insured with the Canton Company, Sydney, for £150, but as this was nothing near her true value, Mr Longworth was a loser to the extent of fully £300 or £400. She was being brought to Newcastle with the intention of running in the Hunter River trade.

ON the night of Saturday 20 August 1881, a serious collision occurred outside Nobbys Head, Newcastle, between the Duckenfield and the SS Boomerang. The Duckenfield was bound inwards from Sydney. She ran into the Boomerang which was outward bound, striking her on the port quarter and carrying away the whole of her sternto within 2 feet of the water's edge. The Duckenfield escaped with only a small hole in her starboard bow. The Boomerang returned to port.

On Friday 30 September 1881 the Newcastle Marine Board handed down their decision as to the causes of the collision between the Duckenfield and the Boomerang. They considered that the Captain of the Duckenfield committed an error of judgment and that he was deserving of censure.

On Saturday 22 October 1881 the Duckenfield was towing the barque Albyn's Isle into Newcastle when the hawser parted while they were crossing the bar. There was a "terrible" sea running and the barque drifted rapidly towards the beach. The tug Goolwa steamed out and "cleverly" rescued her before she went aground.

On Thursday 14 December 1882 Mr Justice Windeyer gave judgment in the matter of the collision between the Boomerang and Duckenfield, off Nobbys on Saturday 20 August 1881. The owner of the Boomerang instituted a claim for damages against the Duckenfield, which it contended had caused the collision. His Honor said it appeared the master of the Duckenfield was in no wey responsible for the collision and ruled that the blame entirely rested with the Boomerang. He dismissed the suit with costs.

At 3 am on Tuesday 15 May 1883 the Duckenfield left Newcastle under the command of Captain J. Petherbridge. She had in tow the barque Mary Evans which was under the command of Captain Scaplehorn. The Mary Evans had a cargo of coal. Captain Scaplehorn later told a reporter that after rounding Nobbys Head the wind was about west and blowing moderately, but showing signs of freshening. There was a very heavy sea. The further southward the vessels got the weather became worse. The wind increased and the sea was very rough. At 11 am Captain Scaplehorn called the two men in the watch to go forward with him and "parcel" the tow rope. While the three men (including the captain) were engaged in the work, a very heavy sea broke over the bows and swept the barque from stem to stern.

Captain Scaplehorn and one of the men just managed to secure a hold and saved themselves from being carried away. The other man, James Wilson, was not so fortunate as he disappeared in the raging waves. The Mary Evans at this time was going between six and seven knots. It took about 20 minutes before the crew on the Duckenfield could be attracted and advised of what had happened. It was thought that the unfortunate man must have been some miles away when the engines were stopped. The sea was so heavy and the weather altogether forbidding, that it was deemed a useless risk of life to get the boat out and send men away in her. After remaining for about 20 minutes, and no trace whatever of the missing man being seen, the passage was resumed. Heavy weather was experienced right up to Sydney Heads which were entered at 7 am on Wednesday morning. James Wilson was 45 years old and a native of Sweden. It was

not known whether or not he was a married man.

On Friday 21 November 1884 the Duckenfield was sent out of Newcastle to look for the missing vessel SS Hero. The Hero was reported to have broken her propeller shaft while on a voyage to Fiji.

For the next four and a half years, the Duckenfield worked at her trade without problems. On Friday 24 May 1889, the Duckenfield left Newcastle for Sydney. As well as her usual cargo of coal and coke, the Duckenfield was carrying 50 tons of copper ingots, in transit from South Australia to London. The skipper of the ship was Captain Thomas Hunter. He had been in charge of the Duckenfield for six years, doing more than 600 voyages.

As the Duckenfield passed Broken Bay, heavy rain began to fall and the land was lost from sight. At 7.00pm, the ship approached Long Reef and a few minutes later the Duckenfield was aground on the rock platform. Although the ship was on the shore, the water was 60 feet deep under the bow and already two feet of water was in the engine room.

The ship was abandoned and all crew safely left the vessel in the lifeboats. Picked up by the Hawkesbury, the crew arrived at Watsons Bay in Sydney Harbour at 10pm. The Marine Board of Inquiry found that "the Duckenfield was lost by the wrongful act or default of Thomas Hunter, the Master, in navigating too close to the coast and approaching Sydney from the northward without opening out the South Head light". His certificate was suspended for six months. This was not to be the last incident involving Captain Hunter. Just over a year later, on 14 July 1890, the SS Royal Shepherd, also under the command of Captain Hunter, sank as it left Sydney Harbour.

The cargo of copper was quite valuable, so an attempt was made to salvage it. The Duckenfield had slipped off Long Reef and a week after the accident, a search showed two masts sticking out of the water in 80 feet north of Long Reef.

On 11 June (18 days after the sinking) the masts could not be found but on 18 August one mast was sighted. Two buoys were tied to the mast and a team of salvage divers from the Sydney Marine Underwriters' Association under the direction of Captain John Hall began to salvage the copper from the wreck. The two divers used, Arthur Briggs and William May, recovered 32 tons of copper from the wreck over a week's work. The same team salvaged 69 ships over a 13 year period, the most famous being the recovery of gold from the wreck of the SS Catterthun off Seal Rocks in 1895/6.

| |

A satellite photograph of the coast north east of Long Reef showing the location of the scuttled wrecks

The SS Duckenfield is clearly identified | |

|  |

South-western Mark

Click to enlarge | North-western Mark

Click to enlarge |

Click here for a link to an interactive 3D model of the wreck.

The Duckenfield was lost to knowledge from 1889 till it was rediscovered by Alan and Neil McLennan almost 100 years later in 1987. On 24 May 1989, exactly 100 years after the sinking, the McLennans released details of the wreck to the diving public in a gala event at the University of NSW. The GPS Reading for the wreck is 33° 43.0981' S 151° 19.4277' E (using WGS84 as datum). See my GPS Page for what this may mean. Use the marks at left. Run around and when the you get a really big bump on the depth sounder, drop anchor.

|  |

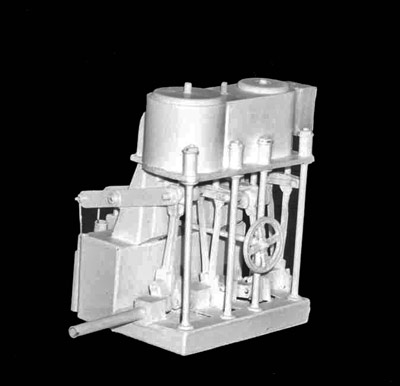

Photos of a model of the engine created by John Riley

John Riley Memorial Collection, Heritage Branch, OEH |

The wreck lies roughly north-south, with the bow towards the north. The wreck today is extremely broken up (understandable considering Briggs and May used explosives to remove the copper). The main features remaining are the lower section of the hull together with the ribs.

You should be anchored somewhere near the boiler or engine. As soon as you descend you should hopefully see the twin cylinder engine which sits up a fair bit off the wreck and is the most prominent piece of the wreck. The driveshaft extends out of the engine and a single blade of the propeller lies just past its end. The engine makes a great photograph, especially if you use the driveshaft in the foreground.

Further on is a section of the driveshaft at right angle to the lay of the wreck and further on is a large winch. Past here is the rudder. Strangely, the main section of the prop lies at the opposite end of the wreck.

|  |

| Kelly McFadyen and the boiler of the SS Duckenfield | Kelly McFadyen and the engine of the SS Duckenfield |

A short distance away to the north-west of the engine is the boiler. This is not all that big considering the size of the ship (it is similar sized to the SS Tuggerah but the SS Tuggerah has two boilers, both of which are much larger). Next to the boilers is the smaller donkey boiler.

Further up the wreck is a winch and in this area the remaining copper ingots lie. Past here there are two anchors from the salvage effort and nearby is the bow section. Here there are the ship's anchors as well as the chain and a davit.

The wreck is very interesting, and can easily be seen in one dive given its 23 metre maximum depth.

|  |

The driveshaft of the SS Duckenfield

and the engine in the background

This cuttlefish attacked my strobe for the whole dive in April 2007 | A winch of the SS Duckenfield, located towards the stern

This cuttlefish attacked my strobe for the whole dive in April 2007 |

You used to need a permit to enter the Protected Zone but in about 2004 this was removed.

References:

|

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005