|

History

On 29 April 1903 a new ship was launched at the Low Walker shipyard of Whitworth & Co Ltd at Newcastle-on-Tyne, England for the Adelaide Steamship Company (ASC). It was named SS Yongala by Miss Adamson, daughter of Mr H Adamson, Superintendent Engineer for ASC. The name of the new ship came from a small town in South Australia located about 250 kilometres north of Adelaide. The correct pronunciation of the town is Yong-gola rather than Yon-gala, but the ship has been more commonly called Yon-gala.

SS Yongala was 363 feet (c 109 metres) long, 46.25 feet (c 13.9 metres) wide and 30 feet (9 metres) deep. She displaced 3,664 gross tons. Power came from a five cylinder expansion steam engine built by Wallsend-Shipway Engineering Company Limited. The steam was provided by five coal fired boilers. She was a passenger and cargo vessel built primarily for the Fremantle (Western Australia) to Sydney run.

The Yongala left Southhampton (the port for London) on 9 October 1903 and travelled via Las Palmas in the Canary Islands to Cape Town. She left there on 9 November 1903 and arrived in Fremantle on 23 November 1903. The ship had first and second class accommodation, with room for 110 and 130 passengers respectively. Photographs show a very attractive looking vessel, inside and out.

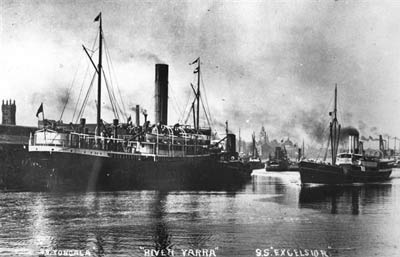

|

| SS Yongala, probably on Sydney Harbour |

From Fremantle, the Yongala sailed to Adelaide (Largs Bay) setting a new speed record. Her average speed was 16 knots. From here she sailed on 1 December 1903 to Melbourne and onto Sydney (6 December 1903).

Her maiden commercial trip started on 2 January 1904 when she left Sydney for Fremantle. For three years she (and her identical sistership SS Grantala) did this run.

In early 1906 the Yongala's run changed to include travelling to Brisbane after Sydney. However, in winter, the trade on this run was not enough to sustain the operation, so May 1907 she changed to run from Melbourne to Cairns. By this time, Captain William Knight was in command of the ship.

The Yongala remained on this this run for the rest of her career.

Sinking

At 4 pm on 14 March 1911, SS Yongala left Melbourne on her regular run to Cairns. Although there were 72 passengers on board, only two would still be on board when the fatal end came. After a crew change in Sydney, she departed at 4:35 pm on 18 March 1911 and arrived in Brisbane on the morning of 20 March 1911.

|  |

| The Yongala in Melbourne | A closer shot of the Yongala from the stern |

After loading and unloading cargo and passengers, the Yongala left Brisbane on 21 march 1911 (probably at 2 pm). An hour later the SS Cooma left Brisbane and off Lady Elliott Island the next day, she passed the Yongala. On the morning of 23 March 1911, she arrived at Flat-top Island (Mackay's then port). At 1:40 pm she departed for Townsville, 208 miles away.

Around 6 pm the Yongala was sighted passing Dent Island (by the lighthouse keeper). However, what Captain Knight did not know was that there was a cyclone approaching Townsville. As they did not have radio, they had no warning of the severe storm's existence. Of course, once they left the relative shelter of the Whitsunday Islands the winds and seas would have increased dramatically.

A few hours after the Yongala left Mackay, her sistership SS Grantala left Townsville. When she was near Cape Bowling Green, the seas were so bad the skipper, Captain Sim decided to turn back and took shelter behind Cape Bowling Green. Meanwhile, the Yongala continued north into increasingly bad weather and seas.

The winds changed from SSE to SW to S and then NW and increased to 70 to 80 mph. It is estimated that the Yongala arrived near Cape Bowling Green in the early hours of 24 March 1911. No-one knows exactly what happened, but whatever happened, she sank roughly 11 miles off Cape Bowling Green.

When the Yongala did not arrive in Townsville at the scheduled time of 6 pm on 24 March 1911, it was obviously assumed that she had sort shelter along the way and would arrive sometime later. Meanwhile, the Grantala resumed her journey south at 8 am, meaning she would have passed almost over the Yongala an hour later.

|  |

| Captain William Knight, skipper of SS Yongala | Another photo of the Yongala |

When SS Cooma arrived in Townsville on the morning of 25 March 1911 and reported that she had not sighted the Yongala, concern was raised. The Adelaide Steamship Company was informed by the harbour master and they sent two ASC vessels from Townsville to search for her. These were the SS Tarcoolaand SS Ouraka. They searched as far south as Dent Island without seeing anything.

On 28 March 1911 it was reported that a bag of chaff branded Lyall, Geelong and a bag of pollard (no idea what this is) with a brand CSR over top of the letter B had been found by the Cape Bowling Green lighthouse keeper. These were the same as cargo been carried by the Yongala. Soon more wreckage was found which made it almost certain that the ship had sunk.

There would be no evidence to show where exactly the Yongala had sunk, other than it must have been in the area near Cape Bowling Green, although some thought it must be on the outer reef. Missing were 72 crew, 30 First Class and 19 Second Class passengers, giving a total of 121 dead (note that this is one more than reported at the time as a child was not included on the passenger list).

Discovery

The wreck's location remained unknown till 1943 when during World War II, a minesweeper found an object 11 miles from Cape Bowling Green. They determined it to be a reef, but this was of course not correct. In June 1947 HMAS Lachlan and tender Brolga were working in the area and determined that it was a wreck, not a reef. Nothing was done to validate that this was indeed the location of the Yongala.

|

| A model of the SS Yongala that is in the Townsville Maritime Museum |

In July 1958 Bill Kirkpatrick searched the area for a few weeks using MV Australia and MV Cooma. On 1 August 1958 he found the wreck. Returning to Townsville, he looked for a diver so he could salvage the wreck. In mid-September 1958 he met George Konrat, a 35 year old German harbour and salvage diver employed by the Townsville Harbour Board. Soon they went out and Konrat dived on the wreck and confirmed that it was the Yongala as he found the ship's name on the bow. He also claimed that the bow was damaged as if a ship had hit it. This was discounted by most.

Salvage

It seems that Kirkpatrick and Konrat fell out as no salvage was undertaken. Soon after this some Townsville members of the Queensland Underwater Research Group (QURG) became aware of the discovery and contacted Kirkpatrick. After convincing him that their scuba equipment was more suited to exploring a shipwreck than hard hat equipment, they dived the wreck.

Over the following three weeks, five members, Don McMillan, Don Gibson, Peter Goadby, Norm Wheatly and Noel Cook dived the wreck (although an article in the April 2024 issue of DIVE Log about the 705th anniversary of QURG claimed only four members dived the wreck). They reported that contrary to Konrad's claims, the ship was undamaged. They also reported that they could not find evidence of the ship's name on the bow, again contrary to Konrat's claim.

The QURG members believed that the wreck was the Yongala, based on the superstructure of the wreck and ship. Konrat announced that he had someone who was financing his salvage bid and that he was going to raise the wreck. After this nothing further was heard from him and it is unknown why he did not proceed with the salvage attempt.

|  |  |

Wally Gibbins with the bell of SS Yongala.

Photo taken at Coffs Harbour, probably by

John Harding (sorry, tried to contact you to seek

approval but your web site has no details) | The bell of SS Yongala that

is in the Townsville Maritime Museum | A porthole from the Yongala that

is in the Townsville Maritime Museum |

On 4 October 1958 a safe was brought to the surface by the QURG divers. They had noticed it on earlier dives. It was opened the next day, but all that was inside was a black sludge, a couple of keys and a corroded paper clip! The safe was actually the key to confirming that the wreck was the Yongala. The safe had a serial number which was partially readable. This was sent to the manufacturers of the safe back in England. They confirmed that it was the safe installed on the Yongala.

In the early 1960s Doug Tarca applied to ASC for salvage rights. They indicated that there was no objection to him salvaging it. However, it appears that he could not refind the wreck. In August 1974 with some others, he found the wreck. When they dived it, they found that the propeller had already been removed. Tarca said that there was some disturbance to the growth on the hull and that he suspected that the work had happened two or three years earlier.

In fact, in 1971 the salvage vessel Radar while travelling to Papua New Guinea to salvage World War II wrecks stopped at the Yongala. They salvaged the eight ton prop. This may have also been when the bell was salvaged. This appears to have been done by Wally Gibbins as he certainly owned it in the period before his death in 2006. There is a bell in the Townsville Maritime Museum but it is unclear if the bell is the same one Wally Gibbins had.

Tragedy and Controversy

On 22 October 2003 two American divers, Gabe and Tina Watson visited the wreck on the first day of a dive trip with Mike Ball Expedition's Spoilsport. The Watsons were on their honeymoon and this week was supposed to be the highlight of their trip to Australia.

Gabe had been certified seven years before but had only done just over 50 real dives, most of which had been under the supervision of an instructor, including all his ocean dives. Tina had learnt especially for this trip and had never dived before in the ocean, let alone on a wreck that is relatively deep and subject to very strong currents. By the code of practice adopted by Mike Ball Expeditions (enforceable under Queensland law), neither Tina nor Gabe should have been allowed to dive without a divemaster or instructor. There were also many other rules broken that day.

As is nearly always, there was a reasonable current on the wreck that day. After an aborted attempt to dive (caused by an incorrectly inserted battery in the pressure transmitter associated with Gabe's dive computer), a second attempt occurred. Once on the wreck, Tina and Gabe moved away from the descent line along the wreck and Tina started to panic. She was severely overweighted and also appears to have had a BCD that was incapable of holding sufficient air to counteract this weight.

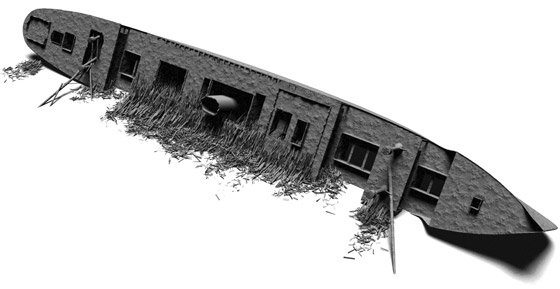

|

| A computer generated 3D image of the SS Yongala |

It also seems that Gabe panicked as well and when Tina knocked his mask and reg out of his mouth and she fell away, he ascended in a vain attempt to get help. Tina sank to the bottom unconscious and drowned.

At first the Police considered the entire thing an accident, with no blame attributed to Gabe at all. In fact Mike Ball Expeditions was prosecuted for breaches of Queensland legislation and in 2007 they were fined $6,500.

In 2007 and 2008 a Coroner's Inquest was held. By this time the Queensland Police had been convinced that it was actually a case of murder. This happened after lobbying by Tina's parents and various US politicians and Police. The Inquest was a farce where so called Police experts produced non-existent evidence and showed that they had no idea about scuba diving. At the conclusion of the inquest, Gabe was charged with murder.

In 2009 Gabe returned to Australia and pleaded guilty to manslaughter relating to a care of duty he had towards Tina (note that this would not have been an offence in any other Australian state and is no longer an offence in Queensland). He served 18 months in gaol before being deported.

Back in the US, he was arrested and charged with murder. In early 2012 his trial for murder was held and I travelled to Alabama to appear as his expert dive witness. Gabe was acquitted of murder at this trial when the prosecution could not produce one witness or any evidence that supported a case of murder.

For more information about this case, click on this link to read my full dissection of what happened.

Diving - General

Today the wreck lies with the bow facing to the north-north-west and at a depth of about 26 metres. It is on a sandy bottom. The wreck is angled over at about 60° on her starboard side. Most of the superstructure has collapsed, with the masts and lifeboat davits on the sand. You will only get about 20 to 25 minutes on the bottom (using air) on a first dive and closer to 20 minutes on a second dive, assuming a 75 minutes surface interval and spending time at various depths. You can certainly stay longer without going into decompression, you just need to keep coming shallower.

Even though there are plenty of easy places inside the wreck to explore, you are not permitted by Queensland law to enter any part of the wreck or even swim under the bow or stern. Presumably this is a misguided attempt to save the wreck from more deterioration caused by divers' air bubbles. One cyclone would do more damage than 10,000 divers bubbles.

The following sonar photographs fairly accurately represent the wreck as of the mid-2010s, except that the bow section forward of the first hold has dropped a little.

|

| A computer generated 3D image of the SS Yongala |

|

| A computer generated 3D image of the SS Yongala |

The wreck is located at a GPS reading of 19° 18' 14.454"S 147° 37' 21.374"E using WGS84 as a datum.

As mentioned above, the Yongala more often than not has currents on it. The depth of 26 or so metres also means that it is not a dive for inexperienced divers. I would suggest that a minimum of 100 ocean dives should be considered to be required to dive it, with quite a few of those at least to this depth and in similar conditions.

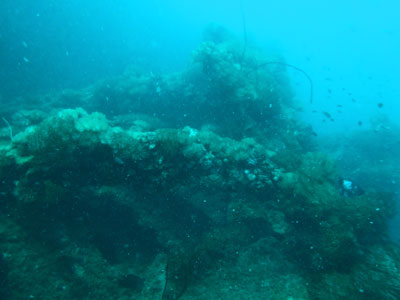

|  |

| The hull of the Yongala looking from bow | The deck of the Yongala looking towards bow |

To dive here, the boats moor on one of the five mooring spots. These are located one forward of the bow, two amidships and two astern of the wreck. There are two descent/ascent lines. One is attached to a block in front of the bow and the other is off the stern. There are lines from these to the wreck itself.

When the boats arrive, they select the most appropriate mooring based on the current and their size. They then tie a line from their stern to the mooring. Most of the currents seem to come from the north, no matter what the tide is doing. On my

five dives here, I have had one dive with virtually no current, two with a slight current, one with a medium current and one with a very strong current. Most times the current goes all the way to the bottom, although at times it may be coming from the north-west (diagonally across the wreck) meaning you can get out of it by dropping below the top of the wreck.

Diving - The Bow

On some dives, due to the current you will only be able to safely dive one part of the wreck. For example, if there is a strong current from the north-west and you enter the water at the bow, you do not want to go to the stern and then have to swim all the way back into the current. Remember, the wreck is 110 metres long.

|  |

| The forward mast looking towards the stern | A leopard shark at the bow |

|  |

| A bullray near the sand at the bow | Looking from the second hold into the passenger area |

Once you are on the bow descent/ascent line, you will see that at 10 metres a line comes off and heads to the wreck. Do not drop below this as you will end up on the sand. Follow the line over to the wreck and you will be at about 14 metres or so. This is just behind the bow and in good visibility you should be able to see it.

If the current is very strong and you are concerned about it, stay in this area, holding onto the wreck. The fishlife here will be more than adequate to make the dive memorable. In favourable conditions, start dropping towards the sand and you will soon see the first hold. If you look carefully you will see that the bow section has dropped a little. The forward mast now hangs out over the sand point off at 45° to the left a you approach. This area is where Tina Watson was found lying.

Past the holds you will see where the mast comes from the superstructure. Behind this there is another larger hold. The main superstructure starts aft of this. As mentioned, the upper sections have collapsed although parts of the lower level are still intact. The bridge would have been in this area. There are plenty of holes that you can look inside, but you will need a torch to light up the darker parts.

|  |

| Part of the engine | Some davits from the starboard side |

|  |

| A large cod | Looking through a former porthole into the main part of the wreck |

A few metres on is the hole where the funnel stood. This is probably as far as you want to go on a first dive or in any reasonable current. Come back a bit shallower and this time drop into the holds, making sure that you have nothing above your head (so you do not break the law). If you drop into the second hold, just before you do you can look towards the stern and see back into the main passenger sections of the ship.

Continue back to the bow. Once here, if there is little current examine the anchor hanging in its hawser under the bow. You used to be able to see the ship's name on the upper hull, but it now seems to be covered in growth (and presumably it is illegal to clean it). If you have air and are not in deco, stay here till you need to ascend.

The one thing I have not mentioned yet is the marine life. This wreck has more life than any wreck or reef I have ever dived before. It is literally covered in it. Things you will see are huge Queensland gropers, we saw a number, one which was, as they say, the size of a VW. There are also hundreds of giant trevally, huge bullrays (we saw at least six on the one dive) and eagle rays (12 seen at once).

There are also plenty of turtles, you will see them resting on the wreck or sand and coming up for air when you are on the boat. There are plenty of barrcuda hanging over and off the wreck and all the normal tropical fish. We even saw a leopard shark at the bow one dive.

The wreck itself has lots of sponge and coral growth, with plenty of gorgonias. There are anemones and clownfish to see as well.

Make sure you have plenty of air if there is any sort of a current as you may need to to get back to the boat. Once you decide to ascend, go up to five metres and do a good safety stop of at least five minutes. If the current has picked up while you are down, you may have to pull yourself back to the boat. I can tell you that in a very strong current this is hard and uses lots of air.

Diving - The Stern

From the stern descent/ascent line, drop over onto the stern. You can see that the prop is missing, taken in the salvage works. The rudder is also very obvious. There is a large mast running out over the sand from here. Forward of this is the rear hold. Again, you can drop into the hold and get some good views forward.

Moving towards the bow you will soon see a large opening. This is the engine room. If you look carefully you will see the engine. This is a large five cylinder triple expansion steam engine (in O0o0O configuration), not a very common type of engine (SS Cities Service Boston in NSW and the German WWI wreck SMS Cormoran in Guam have one).

From here if you go forward you will come to the funnel hole. This is as described in the bow dive above. You could go a bit further if the current is not too strong. In fact, on a couple of dives on the wreck we did go all the way from bow to stern and back and from stern to bow and back. On these dives there was little current.

|  |

| Another bullray on the wreck | A turtle on the rear mast |

|  |

| Two eagle rays high over the bow area | The two eagle rays come in close |

Again, to keep within no-deco times, you can come to the top of the wreck which ranges from 15 to 18 metres deep depending on where you are. For example, the bow is a bit deeper than further back.

As with any dive on the wreck, the fishlife is simply amazing. I wrote about one dive that it was the best dive I had done for many years. To be honest, even the worst dive on the Yongala is a great dive.

Summary:

As I pointed out, this really is only a dive for the experienced diver (and I do not mean one with 50 dives). When the current is running it can be a scary dive and on my trip we abandoned one dive as the current had picked up to be extremely strong.

When I dived here in November, the water temperature was 26° to 27°C and the visibility varied from dive to dive, even on the same day. Viz was between 7 and 15 metres.

DIVES

17-Nov-14 - 3

22-Nov-14 - 2

22-Aug-15 - 4

23-Aug-15 - 2

NOTE:

The sonar photos were provided by a company called Xplore Dive but this seems to no longer exist.

MORE INFORMATION

Well known Sydney wreck diver, Max Gleeson has published two books on the Yongala (S.S. Yongala Dive to the Past - 1987, S.S. Yongala - Townsville's Titanic - 2000) and in 2018, a video (S.S. Yongala - Mystery of a Generation). You can contact him via his web site.

|

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005

v6.00.307 © 2003-2005